The Torah content for these two weeks has been sponsored by Ariel Rachmanov, a friend and Mishlei talmid of mine. Ariel works for Keller Williams Real Estate and has generously offered to donate to the Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund a percentage of any business that comes his way as a result of this sponsorship, resulting in a Mishleic "win, win, win" scenario for all parties involved. Ariel is based in New York but will be happy to help you meet your real estate needs in all 50 states.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this article, and click here for an audio version.

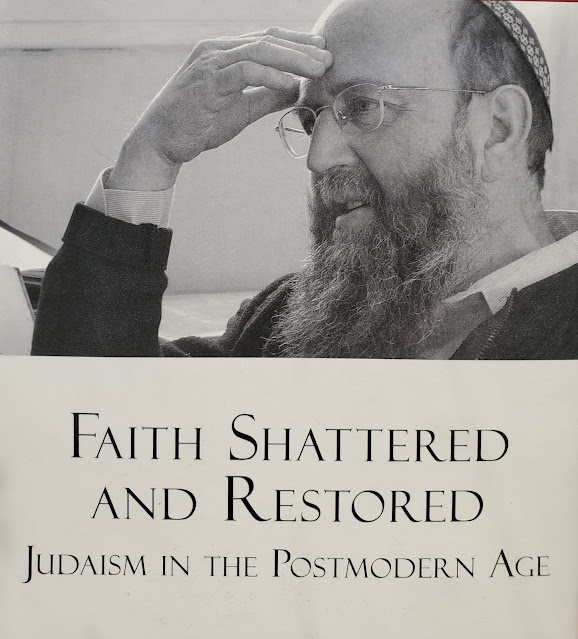

Preface: In the summer of 2021 I started writing book reviews for all the non-fiction (and some fiction) books I read. I post these reviews on Facebook (in a publicly shared photo album, which you shouldn't need a Facebook account to view) and in my WhatsApp Book Review group (email me if you want to join). Most of these reviews are relatively short. However, at the beginning of this summer I was exposed to the writings of R' Shagar for the first time through this book. The resulting book review ended up being less of a review and much more of an essay about my first impressions of R' Shagar's overall approach. Because I have referred to his ideas in earlier articles and will likely do so in the future, I decided to share the entire review here.

Translated from the Hebrew by: Elie Leshem

Editor: Rabbi Dr. Zohar Maor

Publication Date: 2017

Genre: Jewish philosophy

Length: 225 pages (including the 18-page preface)

Status: read for the first time in June 2022

Disclaimer for those who are new to my book reviews or who need a reminder: these should be regarded as nothing more than my PERSONAL reflections and impressions. They are intended to capture what I thought about the books I read shortly after reading them. They are primarily for myself in that they allow me to process what I’ve read – something which I can best do by sharing my thoughts with others. They are not intended to be scholarly articles. If you are looking for a professional review, by all means look to the professional academics and intellectuals – beginning with the comprehensive afterword written by the eminently qualified Rabbi Shalom Carmy.

Note: This book review will be longer than the ones I usually write because I have a lot to say. For this reason, I've decided to divide this into subsections with titles. Buckle up.

I. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

If I had to answer the question: “So, what did you think about this book?” in a single sentence, that sentence would read: "Regardless of what I think about R’ Shagar’s IDEAS, I wholeheartedly support what he was DOING."

Before I elaborate on that sentiment, I think it would be helpful to start by addressing the subtitle of the book: Judaism in the Postmodern Age. Almost everything I know about postmodernism (which is not very much) I picked up through osmosis – more from social media, YouTube videos, and podcasts than from books. Before I read this book, if you had asked me, point blank, what postmodernism is, I'm not even sure I could provide a clear answer. Thankfully, a clear definition is supplied by Aryeh Rubin in his preface (with my emphasis in the underlined portion):

As noted, the heart of the book is Rabbi Shagar's grappling with postmodernism and the cultural and spiritual changes it wrought. In chapter 5, he attempts to get at the foundations of postmodernism: the denial and deconstruction that come from the erosion of belief in any "grand narrative" and in the ability to perceive the truth. Rabbi Shagar distinguishes between "hard" and "soft" postmodernism: While the first leads to utter nothingness, the second does not deny the existence of truth and goodness, but claims that these values are not predetermined, but rather man-made; hence their relativistic nature. According to Rabbi Shagar, the first brand of postmodernism should generally be rejected ... Rabbi Shagar devoted most of his efforts to exposing the positive in soft modernism, which does not necessarily lead to nothingness in that it recognizes beingness – albeit as a human construct (which is thus dangerous in that it can engender relativism and even contempt for morals, norms, and responsibilities).

I am not a postmodernist, but I concede that we are living in an increasingly postmodernist age. I also concede that this recent revolution has given rise to new questions, difficulties, and crises which cannot be adequately addressed by the prior models and thinkers of Modern Orthodoxy, especially by those who are unaware or unwilling to admit that such a drastic paradigm shift has taken place. Moreover, I have seen an increasing number of Orthodox Jews - my age and younger - whose beliefs and/or observance have been shaken or threatened by postmodernist problems, even if they haven't consciously identified them as such. As an educator, it behooves me to familiarize myself with postmodernism for the sake of my students, even if not for my own sake (not that I'm ruling this out, mind you, knowing how formidable postmodernist thinking can be). That was the reason why I chose to read this book at this time. That, and the fact that R’ Shagar’s name has been mentioned by a number of individuals from diverse backgrounds whose minds I respect.

In an ideal world, I would "go forth" and educate myself about postmodernism from firsthand sources. The reality is that I have neither the time nor the interest nor the intellectual processing power to embark on such an immense project. Just as I was happy to allow Mortimer J. Adler to be my introductory guide through Western philosophy up to the 20th century (especially through his excellent book, Ten Philosophical Mistakes), so too, I am happy to allow R' Shagar to be my introductory guide through the alien world of 21st century postmodernist philosophy. And just as I was aware that Adler had his own agenda, as an independent thinker and teacher, I am aware that the same is true for R’ Shagar. The words of all such minds should be taken with a grain of salt.

This book was my first exposure to R’ Shagar. Prior to reading this book, the only thing I knew about R’ Shagar was from hearsay on social media. The impression I had was of a radical, innovative, and controversial genius. After reading this book, I can see why. To borrow a line from R' Soloveitchik from my beloved Footnote 4 of Halakhic Man (rendered into beautiful English by Professor Lawrence Kaplan), the path R' Shagar has taken is "not the royal road, but a narrow, twisting footway that threads its course along the steep mountain slope, as the terrible abyss yawns at the traveler’s feet." It would not be an exaggeration to say that this book is a minefield within a minefield.

Rabbi Carmy acknowledges the enormity of R’ Shagar’s mission: “Jewish thought must boldly go where it has not gone before, both in our analysis of the social world and in proposing fresh ideas about how to live our lives in light of these new experiences.” He also acknowledges the gaps and dangers in R’ Shagar’s philosophy: those inherent in his way of thinking as well as those created by the incompleteness of the legacy he left behind. He writes: “That is not to say that his theses are beyond criticism … In particular, one must be wary of the solipsistic dangers in his sometimes unquestioning reliance on self-acceptance as a key to moral and religious truth and the concomitant downplaying of divine transcendence. That Rabbi Shagar himself seems intermittently aware of these problems himself … does not exempt us from struggling with them on our own.” (Again, I recommend reading Rabbi Carmy’s entire afterword, and making sure to read between the lines, such as his careful use of the word "intermittently" in the foregoing sentence.)

I can understand why a religious Jew would be tempted to push R' Shagar away with both hands. If I may be permitted to butcher a culinary analogy: R' Shagar has taken upon himself the task of extricating Judaism from the fire of nihilistic "hard postmodernism" only to throw it into the frying pan of "soft postmodernism." I sympathize with those who exclaim: "I don't want Judaism in the frying pan OR in the fire! Just get it out of the kitchen!" but for many, that ship has already set sail.

To restate my earlier point in the language of this new idiom I just coined: Judaism is already "in the kitchen.” We may not get to choose whether the Judaism of our children, our students, or ourselves is thrust into postmodernism’s fire, but if that happens, it's good to know that there is a knowledgeable and talented chef who might be able to save it from the flames and, by introducing us to the proper frying techniques, help us to prepare a delicious meal. ::: end of egregiously awkward mashal :::

II. MY GREATEST TAKEAWAY

Even though I am not a postmodernist, this book helped me to realize that there is a surprisingly large overlap between my own epistemology and what R’ Shagar refers to as soft postmodernism. The most important shiur I gave in the 2020-2021 year was titled Of Wolves, Men, and Methodology: An Attempt to Capture and Articulate an Epistemological Upheaval. The shiur examined the limits of human knowledge and warned against unwarranted reductionism and its attendant fallacies – ailments to which the so-called “rationalists” (as people have often labeled me … libeled me?) are particularly prone. That shiur marked a vitalizing revolution in my intellectual and spiritual life which was augmented by my reading of Eastern-influenced Western-trained psychotherapists over the course of that summer. I sense that R' Shagar will usher in the next part of that exhilarating personal journey.

Allow me to stress some fundamental differences in order to better highlight the similarities. The postmodernist thinks we CANNOT know truth, whereas I think we CAN know truth, albeit very little and with very little certainty. The postmodernist regards man-made narratives and theoretical constructs as worthless and harmful insofar as they prop up the illusion that truth is real and attainable, whereas I regard these as the only truth-seeking tools we have at our disposal, making them valuable and necessary. The postmodernist sees the reductionist fallacies I outlined in my Wolves shiur to be lamentably and inescapably hard baked into my “modernist” “rationalist” “realist” worldview, whereas I see them as pitfalls that can be diminished or avoided with proper vigilance.

What interests me is this overlapping space between my “(moderate) modernist rational skepticism” and R' Shagar’s “postmodernist (radical) skepticism.” Despite my being a Modern Orthodox Jew and him being a “Postmodern Orthodox Jew” (a term he didn’t use but which I find useful), we see eye to eye on the need to free ourselves from misplaced feelings of certainty. Of course, I’d say he’s gone too far while he’d say I haven’t gone far enough, but both of us would congratulate each other on the steps each of us have taken in our respective journeys. I sense that there is much common work that can be done in this shared space, despite our epistemological differences, and I am eager to dig into that work. The awareness of that space in all its richness is, I believe, my greatest takeaway from this first exposure to R’ Shagar’s thinking.

III. ANOTHER COMMON FEATURE

Throughout these essays R’ Shagar exhibits a quality which I feel makes us kindred spirits: our intellectual eclecticism. Both of us seem to have a wide range of interests in our reading. Both of us are unabashed when it comes to using what we read to enhance our understanding of Judaism, regardless of its source. I, too, admire Slavoj Zizek and have quoted his ideas while rejecting other elements of his worldview.

My own brand of eclecticism stems from three related sources: (1) my rootedness in the teachings of Bruce Lee, the innovator of the styleless style whose motto was "using no way as way, having no limitation as limitation” and whose mantra was “efficiency is anything that scores,” (2) my personal striving to embody the ideal of, "Who is wise? One who learns from everyone," and (3) my firm conviction in the universality of truth and the common tzelem Elokim nature shared by all human beings.

According to Rubin, R' Shagar's eclecticism stems from his view that "it is faith, of all things, that can redeem postmodernism by imbuing human constructs with new value and validity, as vessels for the divine light" and "can also foster a humility and tolerance capable of greatly enriching the religious outlook." This soft postmodernist lens allows Shagar to see the potential for value and meaning (I almost said “truth”!) in everyone and everything, and encourages a healthy level of discourse founded on mutual respect.

R' Shagar’s essays helped me to articulate an advantage I have as a non-postmodernist teacher in a postmodernist world: the combination of my eclecticism and my belief in the value of every human intellect allows me to connect even with those who deny the entire enterprise of truth-seeking. I was dimly aware of this before reading this book, but I lacked the vocabulary to name it.

IV. MY BIGGEST QUESTION AND R’ SHAGAR’S ANSWER

There is one question that was raised by Rubin in the preface which generated some high expectations on my part:

The religious person's challenge in the postmodern world is to choose and believe in his path, and to trust his creative powers. Paradoxically, Rabbi Shaar argues, it is easier to maintain a religious lifestyle in a postmodern world. For while modernism was characterized by an onslaught against religion and faith - in light of philosophical and scientific discoveries that were perceived as absolute truths - postmodernism's skepticism casts religion as an option no less valid than others. The challenge for us as believers, of course, is to choose religion as the best option.

To translate this challenge into a question: Is there a compelling reason for a Jew in a postmodern era to choose Orthodox Judaism? As I alluded to above, this question is of the utmost importance to me as a teacher of students who were born and bred in a postmodernist age. I didn’t know at the outset of my reading whether Shagar would address that question explicitly, but I sincerely hoped he would, and that his answer would be either true or useful.

Thankfully, R’ Shagar did offer a clear answer to this question. I’m not going to do it injustice by attempting to summarize it here. Instead, I’m going to talk around it. To those who are familiar with his answer, feel free to discuss this with me in private. To those who aren’t, I hope my cryptic treatment will tantalize you enough to read the 3.1 essays in which his answer is most clearly spelled out. (I’m referring to essays #2, #3, #5, and two pages near the end of #8.) Feel free to skip the remainder of this section.

I was surprised and somewhat delighted to see that R’ Shagar’s answer bears a striking resemblance to my own understanding of Sefer Koheles, which I have taught for the past eight years, and which forms the basis of my own limited brand of Jewish existentialism. Those familiar with my high school Koheles curriculum (which, unfortunately, is not available in any written, audio, or visual form) will recognize R’ Shagar’s answer as Stage 7 of my “Nine Stages of Koheles.” He even expresses his solution to the question of religion in an almost identical manner to how I express my solution to the question of happiness. The difference, of course, is that whereas I hold by the existence of Stages 8 and 9, which are decidedly "modernist" and "rationalist" in character, R’ Shagar regards Stage 7 as the end of the road. For him, “there is no spoon” is the end of the movie; for me, seeing past the illusory spoon is a step on the road to grasping the reality of the Matrix. (Yeah, I went there.)

Does R’ Shagar provide an adequate answer to the question mentioned above? I would say both “yes” and “no.” My realization of the “yes” came from a thought experiment I conducted on my Shabbos afternoon walk, which I took after reading the first seven essays. I asked myself, “If I suddenly became a postmodernist who denied the existence of truth or man’s ability to know it, how would I live?” My honest answer to that question – which I arrived at by setting aside everything I had read – ended up aligning with R’ Shagar’s approach. (I also asked myself, "And given that you're not a postmodernist, what relevance do you see in R' Shagar's answer?" The answer to that question was: "Quite a lot of relevance" ... but that is a topic for another time.)

As for the “no”: sadly, I doubt that R’ Shagar’s approach would be compelling enough to keep an on-the-fence Orthodox Jew within the fold, nor do I think his approach could convince a non-religious Jew to become religious. I don’t know what he would say about those two situations, or whether I had the right to expect such results from this book - but expect it I did, and I didn’t find what I hoped to find.

One more word on R’ Shagar’s answer to this question, from the teachings of my rebbi, Rabbi Morton Moskowitz zt"l. Whenever a student made fun of a non-Jewish belief as being “stupid” or fancied themselves superior because of their own conviction, Rabbi Moskowitz would say, “If you were born in Haiti, you’d be sticking pins in voodoo dolls too.” If I could ask R’ Shagar one question in person, that question would be: “What would YOU tell the guy in Haiti sticking pins in voodoo dolls, and would it matter to you if he were Jewish?” I wouldn’t ask him this question out of total ignorance as to how he'd answer. His answer is clear from this book, especially essay #6. I’d ask him this question because of my interest in the discussion that would follow, and because I’d want to see if he really believes his own answer as much as he says he does.

Lest you chastise me for questioning where R’ Shagar stands on his own beliefs, or for wanting to see where he falls out on the spectrum from rationalism to relativism, I’d like to point out that Rabbi Carmy has the same questions.

- He writes: “Rabbi Shagar repeatedly insists that he is not a relativist … nor does he disdain the role of rationality in religious discourse. Much of his philosophy stands or falls on whether and how satisfactorily he explains this position.”

- Likewise, Rabbi Carmy recognizes the danger inherent in R’ Shagar’s pluralism, citing R’ Shagar himself as a support: “A great danger in this approach is that such a faith, emanating from the bowels of one’s selfhood, would not be religious faith, but merely an act of egocentric self-anointment; in Rabbi Shagar’s words, ‘the tendency to turn oneself into the yardstick of reality’ (p.34).”

- Rabbi Carmy also notes the contradictory tendencies in the practical implications of R’ Shagar’s pluralism: “It may seem paradoxical that he is willing, in principle, to take life in the name of his faith, but forbidden to ‘assert that faith in my own way renders other ways worthless’ (p.117). No doubt, one can speak in mystical terms of complementary categories according to which both universal equality and individual commitment can be justified, and there are other ways of dissolving the logical consistency. At a practical level of human relations, the difficulty nevertheless persists.”

Rabbi Carmy is kind in his phrasing of these criticisms. Rabbi Moskowitz (and Socrates) would put it more bluntly by pointing out these contradictions until R’ Shagar either refined his views or acknowledged his errors. Mortimer Adler might invoke a variant on his statement (cited from memory) about relativism: “You can’t convince a subjectivist of objective truth, but you can convince an honest man that he’s not a subjectivist.” (And yes, I’m aware that R’ Shagar is not a subjectivist, but a Realist with a Lacanian capital “R.”) I don’t question R’ Shagar’s honesty from a moral standpoint. He was clearly a man of integrity and courage. Rather, I question whether there is a fundamental dishonesty lurking at the core of his entire belief system. If there is, it would, according to him (according to Rav Kook), be the worst kind of dishonesty: self-delusion, which arises from self-alienation.

I never met R’ Shagar, but in my imaginary dialogue, this is where he smiles at me and says, “Of COURSE you believe that I’m deluding myself and that, deep-down, I’m a modernist who believes in objective truth, because that’s what YOU are” – at which point, we’d both acknowledge that the discussion could proceed no further.

V. A SHIFT IN MY VIEW OF HASIDISM

The most unexpected effect that this book had on me will probably upset some people. Actually, "upset" might be the wrong word. Either “offend” or "vex" would be more accurate. You have been warned.

It is no secret that I have great reservations about ideas that originate in Hasidism, "Kabbalah" (using quotation marks intentionally), and certain other strands of mystical thought within Judaism. This is not the place for me to spell out these reservations. Suffice it to say, I am skeptical of any innovations within Judaism which stake their claim on the basis of what I’ll refer to as “sketchy revelation claims,” whether in the form of mystical visions, transcendental experiences, or books which appear in 13th century Spain that are claimed to have been authored a thousand years prior in the face of abundant evidence to the contrary. Until now, my reservations have caused me to ignore and resist ideas drawn from these sources – not because I deny their possible value, but because of my deep reverence for Hashem and His Torah (to the exclusion of counterfeits), and because I’d rather devote my time to learning that which does not require any leaps of faith on my part. (Okay, HERE you can call me a "rationalist" and I'll bear that label with pride.)

I can't quite explain how, but SOMEHOW, reading this book triggered an epiphany in me: I can maintain my skepticism about the “authenticity” of these thought-systems while simultaneously finding truth and value in them, the same way I do with non-Jewish philosophies. If I can learn from Plato, Aristotle, and Seneca without embracing these philosophies in their entirety and without labeling them as “Jewish,” why can’t I do the same with R’ Shneur Zalman of Liady, R’ Yitzchak Luria, and R' Moshe de León?

I suspect that this shift in my perspective was due to the fact that some of the ideas which R’ Shagar ascribes to Hasidism – most notably, those of R’ Nachman of Breslov, who stands about as far away from the Rambam as you can get – are strikingly similar to the ideas I’ve found to be enlightening in Buddhism and Taoism. What if I regarded R’ Nachman not as an authentic part of our Mesorah, but as an Eastern thinker who expressed and developed his ideas on a Torah scaffolding with Jewish terminology? I don't know how R' Shagar would feel about my endorsement of Hasidic thought NOT on the basis of its alleged Jewishness, but because it resembles the truth I've seen in Eastern thinking. I hope he'd just flash me a thumbs up and say, "Whatever works for you, man."

VI. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

When I set out to write this review, I told myself that I’d hold back and refrain from writing about any specific ideas in the book. Remarkably, despite the length of this review, I’ve held to that decision. There were many ideas and insights I largely agreed with and plan on writing about over the course of the summer, including (but not limited to) R’ Shagar’s statements about Orthodoxy and Modern Orthodoxy, his theory about what sets Conservative and Reform Judaism apart, his postmodernist approach to analyzing mitzvos, his take on Divine providence, his social commentary on media overload and its effects on our very identities, and more.

Of course, there were also ideas I disagreed with, ideas I flat out didn’t understand, and ideas I simply wasn’t interested in thinking about at this time. I don’t know if this was a coincidence or whether there’s a correlation, but I found that I had a very hard time focusing on ideas which he expounded using either highfalutin academic jargon or highfalutin kabbalistic jargon. Maybe it’s just because I’m not used to operating in those worlds. Regardless, there were enough clear and compelling ideas in the parts of the book I found valuable for me to assume that the parts I didn’t find value in are worth rereading at some point. This is definitely a book that merits multiple rereadings, and which I expect to yield new insights depending on where I’m at in my personal development.

I usually conclude my book reviews with a statement of who this book is for. In this case, I think it would be fitting to first state who this book is NOT for, and to do so by quoting one of R’ Shagar’s favorite thinkers. R’ Nachman of Breslov forbade his students to study or even look at the philosophical writings of the Rambam, warning them that “such works only confuse the mind and implant unsound beliefs which are not in accordance with the wisdom of the Torah.” It has been taught in R’ Nachman’s name that “one can tell from a person’s face if he has studied the Guide for the Perplexed ... because they are bound to lose their tzelem Elokim ... Everyone can see that most of the people who study these works today become total atheists.”

Ironically, the Rambam might very well prohibit the reading of R’ Shagar’s book under the Torah prohibition of “lo sasuru acharei levavechem v’acharei eineichem” (“do not stray after your hearts and after your eyes”) – not because it might lead someone to deny ONE of the fundamentals of Torah, but because it might lead them to deny the reality of objective truth altogether, which (he would likely argue) is even worse. I would not feel comfortable recommending this book to those whose minds have not been directly impacted by postmodernism.

At the same time, we are taught that “[Rav Nachman] himself studied philosophical works from time to time; this is the concept of the journey of the children of Israel through the wilderness ... the place of evil forces ... to trample down the forces of evil ... the very great Tzadik is obligated to go into such works in order to elevate the souls which have fallen there.” I’m not a “very great tzadik,” but as I mentioned in my introductory overview, I think it would be prudent for this generation of Torah educators to inform themselves about postmodernism and its impact on Orthodox Judaism, if not for their own sake, then for the sake of their students. I would feel comfortable – even obligated – to recommend this book to them, provided that they would not be in danger of violating “lo sasuru.”

What about those Orthodox Jews who HAVE fallen under the influence of postmodernist thinking, and whose observance and/or beliefs have been threatened? Would I recommend R’ Shagar to them? I don’t think I can give a general answer to that question. For certain individuals, this could make matters worse. For others, this might be the life raft that saves them – or at least, keeps them within the fold and saves their progeny. [Addendum: I would feel much more comfortable recommending Strauss, Spinoza, & Sinai: Orthodox Judaism and Modern Questions of Faith (2022), which I've nearly finished reading for the first time, but haven't yet reviewed.]

If you’ve made it to the end of this review, then I think one thing is abundantly clear: this was an exceedingly thought-provoking book. If you seek to be provoked in this manner, and have valid reasons for reading it, and are not in danger of violating Hashem's mitzvos, then I recommend it to you.

______________________________

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail.com. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor, you can reach me at rabbischneeweiss at gmail.com. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

Be sure to check out my YouTube channel and my podcasts: "The Mishlei Podcast", "The Stoic Jew" Podcast, "Rambam Bekius" Podcast, "Machshavah Lab" Podcast, "The Tefilah Podcast" Email me if you'd like to be added to my WhatsApp group where I share all of my content and public shiur info.

No comments:

Post a Comment