Your obligation is to the highest point of contribution you can make. I think what happens a lot is that people get caught up in the idea that, “Can I do this thing?” They pretend there’s nothing else going on in their life. The request comes in and they go, “Can I do this? Well, yes, I can do this. I know how to do this. I can make this happen.” That’s not life. That’s non-essentialist junk. That’s just rubbish. The question is, “If I do this thing, what doesn’t get done? What else gets pushed out?”

Friday, July 30, 2021

Simone Biles is My Hero

Wednesday, July 28, 2021

Help! I've Fallen Into Sufi Poetry and I Have No Idea What I'm Doing!

|

| a haiku by 12th grade Matt Schneeweiss |

What you know, you can’t explain, but you feel it. You’ve felt it your entire life … You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad.

Tuesday, July 27, 2021

The Principle of Humanity vs. Emunas Chachamim

[When] interpreting another speaker we must assume that his or her beliefs and desires are connected to each other and to reality in some way, and attribute to him or her “the propositional attitudes one supposes one would have oneself in those circumstances.”

At the outset of your analysis, you should establish as a premise of your thinking that each of the speakers – the one who asks and the one who answers – that both of them are intelligent, and that all their words [were spoken] with wisdom, understanding, and knowledge, without anything twisted or distorted. This is what [the Sages] mean when they [rhetorically] exclaim: "Are we dealing with idiots?!" (Shevuos 48b). Therefore, you must analyze all their statements and see if they are statements with sound reasons, "as strong as a molten mirror" (Iyov 37:18) or whether [they are] weak statements, [like] "bland food without salt" (ibid. 6:6), and whether they are intellectually probable or improbable. One must strive to make their words probable and to adjust their ideational content so that [the statements] will be beautiful and acceptable and intellectually feasible; [one must also strive] not to ascribe to them the guilty iniquity of a tenuous or weak sevara (theory). None of their words should fall to the earth, for they are all "the words of the living God." And if they are "empty," [the "emptiness"] is from you. (Darchei ha’Talmud 1:3)

Monday, July 26, 2021

Taking the Road Less Traveled in Learning

|

| Artwork: Adventurous Impulse, by Minttu Hynninen |

These are the perplexities that have arisen from this powerful question. Regarding the quest for the answer and the resolution [of these doubts] – behold! I remain alone, and no one has worked with me on these [matters]. On this subject I have found nothing – minor or major, good or bad – from our Sages of blessed memory: not from the early Talmudic Sages, nor from the latter authors or commentators. Not even one of them was bestirred by this perplexity at all, nor did any of them pave the way for its answer.Behold! Hashem has added grief to my pain, for we do not have with us in this land a commentary on Sefer Divrei ha’Yamim, except for the few matters authored by the Radak (of blessed memory) which are nullified in their minuteness (batelim b’miutan), and he didn’t investigate deeply at all. Moreover, this book of Divrei ha’Yamim is not commonplace among the Jews in their midrashim.Today I will recall my sin (es chata’ai ani mazkir ha’yom), for never in my days had I read it, nor had I investigated its contents for the duration of my existence until now, and nothing has remained for me but the force of my reasoning and my intellectual intuition about the pshat (straightforward meaning) of the pesukim, and the help of God Who has girded me with success and made wholesome my path.

Friday, July 23, 2021

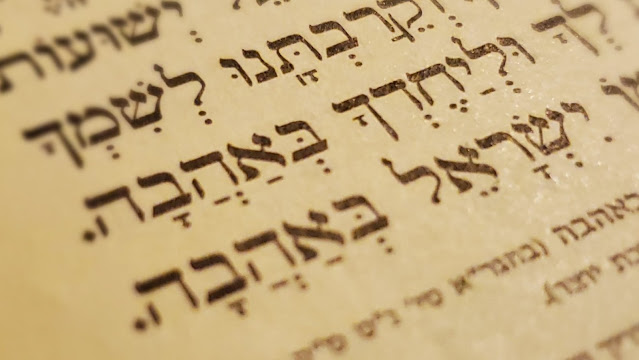

Vaeschanan: Declaring Hashem’s Oneness in Love

This week's Torah content is sponsored by a generous donor who wishes to remain anonymous, and told me, "No thanks needed!" so I'm not going to thank them.

You will find that this berachah includes many themes: that Hashem loves us more than all the other nations, that He gave us the Torah, that He instilled within us belief in His Oneness, and that He is the Lord of all – but the berachah concludes with [the theme of] love, not with [the theme of] Oneness, because the declaration of His Oneness is ineffective (lo yo’eel) unless it is from love and from a whole heart.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

Musings on the Inadequacy of Internet Research

This week's Torah content is sponsored by a generous donor who wishes to remain anonymous, and told me, "No thanks needed!" so I'm not going to thank them.

Namah, the root of namaste, means “I bow to you,” basically meaning, "salutation." All of Asia bows to the other person as a greeting. It is halakhically like “adios” ("God be with you") or “goodbye” (“God be with you”). We pasken (rule) that you can say goodbye and adios. The Nesivos (Rabbi Yaakov Lorberbaum, 1760-1832 C.E.) makes it assur (prohibited) but our poskim (adjudicators), allow you to say “goodbye.” If you Google namaste you will find lots of derashot (homiletics) from Indian religions but they go beyond the peshat (literal meaning).

Now if you awaken a man, even though he were the dullest of all people … and if you were to ask him whether he desired at that moment to have knowledge of [the secrets of reality] … he would undoubtedly answer you in the affirmative … but he would wish this desire to be satisfied and the knowledge of all this to be achieved by means of one or two words that you would say to him. If, however, you would lay upon him the obligation to leave his job for a week in order to understand all this, he would not do it, but would be satisfied with deceptive imaginings through which his soul would be set at ease. He would also dislike being told that there is a thing whose knowledge requires many premises and a long time for investigation.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

Bodily Posture as a Sensory Anchor for Kavanah in Tefilah

This week's Torah content is sponsored by a generous donor who wishes to remain anonymous, and told me, "No thanks needed!" so I'm not going to thank them.

When he stands in tefilah, he needs to place his feet side by side; he should direct his eyes downwards, as if he is looking at the earth; his heart should be faced upwards, as if he is standing in the sky; he places his hands clasped over his heart, the right on the left; he stands like a servant before his master, in awe, fear, and dread; and he shouldn’t rest his hands on his hips. (Hilchos Tefilah 5:4)

[The] path to mindfulness begins with concentration – a one-pointed focusing of attention. It’s difficult to be mindful of your experience if your mind is lost in a continuous stream of discursive thought. So first we collect and quiet the mind by directing attention to a sensory anchor. This might mean following the breath, or scanning the body for sensations, or listening to sounds … With practice, whatever anchor you choose can become a reliable home base for your attention; like a good friend, it will help you reconnect with an inner sense of balance and well-being.

Tuesday, July 20, 2021

My Experience Fasting for 48 Hours on the 9th and 10th of Av

|

| fast began at 8:30pm on Saturday (7/17) and ended at 9:00pm on Monday (7/19) |

It was taught in a Baraisa: "On the 7th of Av the gentiles entered the Sanctuary. They ate and drank and wreaked havoc on the 8th and the 9th until late in the day. Towards the evening they lit a fire in it, and it burned until sunset of the 10th." R' Yochanan said: "If I were there, I would have established [the commemoration] on the 10th, when the majority of the Sanctuary burned." It says in the Yerushalmi that R’ Avin fasted on the 9th and the 10th, [whereas] R' Levi fasted on the 9th and the night of the 10th because he didn't have the energy to fast for the entire night and day of the 10th. Nowadays, our energy has waned, and even Yom ha'Kippurim, which would be proper to observe out of safek (doubt) for two days, we are unable to do. Nevertheless, it is a proper minhag to not eat meat on the night of the 10th and the day of the 10th, but only what restores the soul, which is partial inui (affliction).

Monday, July 19, 2021

The Tenth of Av, Seven Haftaros of Consolation, and Life After the Pain

This week's Torah content is sponsored by a generous donor who wishes to remain anonymous, and told me, "No thanks needed!" so I'm not going to thank them.

Click here for a one-page printer-friendly version of this article, and click here for an audio version.

|

| Artwork: Gift of Estates, by Alexis and Justin Hernandez |

The Tenth of Av, Seven Haftaros of Consolation, and Life After the Pain

The four steps of RAIN involve active ways of directing our attention. In After the RAIN, we shift from doing to being. The invitation is to relax and let go into the heartspace that has emerged. Rest in this awareness and become familiar with it; this is your true home. Now, paying attention to the quality of your presence – the openness, wakefulness, tenderness – ask yourself: “In these moments, what is the sense of my being, of who I am?” “How has this shifted from when I began the meditation?”

And he should not make his tefilah like one who is carrying a burden who casts it off and goes on his way. Therefore, he must sit for a little while after tefilah, and only then may he depart. The early pious Sages would pause for an hour before tefilah, and an hour after tefilah, and they would extend tefilah for an hour. (Rambam: Hilchos Tefilah 4:16)