Foreword

I was

planning on just posting the article I wrote and leaving it at that. But

the more I thought about it, the more I deemed it important to provide the

background information about why and for whom I wrote this article, to tell you

how it was received, and to share my thoughts on its rejection. I think it’s

especially important to provide this context because I’d really like to hear your

feedback on the article.

Here's

the backstory. A few months ago, I was contacted by two editors from a kiruv (Jewish

outreach) organization. After introducing themselves, they told me about their

new project:

We

are looking for credentialed philosophers to write one or two articles from the

following seven themes (or another if you prefer):

Is

there a God? Where did the Universe come from? What is the meaning of life?

What happens to us after we die? What is consciousness? Is there free will? and

What are good and evil?

They

specified the following criteria, in this language:

- Length: 800-1200 words

- Audience: Mostly millennials but accessible to all who have never studied philosophy

- Style: Deals directly with the issue in a universal way (no proofs from any scripture), must use examples from contemporary culture

- Tone: Serious, but fun and a bit sassy (70/20/10)

Despite

my personal stance on kiruv and my not being a “credentialed philosopher,” I told them

with genuine excitement that this project sounds right up my alley, and that I’d

be delighted to write an article or two in July.

I

chose “What is the meaning of life?” as the subject for my first article

because it's a topic I’ve addressed on many occasions throughout my high

school teaching career, but I hadn’t yet written it up in any form. I welcomed

the somewhat restrictive assignment specifications because it would be way too

easy to let an article like this to get out of hand if I had the freedom to write it as I saw fit.

Below is the final draft of the article. The only difference between this and the version

I submitted is the presence of a single paragraph in brackets towards the end –

a paragraph which they liked but felt would be better saved for the sequel. I chose

to include that paragraph here because, as you might have inferred from the

title of this blog post, a sequel will not likely be forthcoming.

After

you read the article, I’ll tell you how it was received. I'll share my own thoughts on the feedback I received and then I'll ask you for your feedback.

The Purpose of Life (According to Maimonides)

Introduction

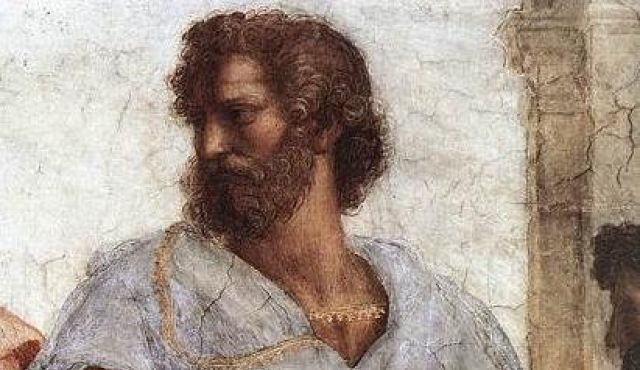

All

religions are expected to answer the question: “What is the purpose of life?”

It should come as no surprise that this question is taken up by Maimonides

(a.k.a. Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, or Rambam, 1138-1204 C.E.), in his Guide

for the Perplexed. [1]

For those

who have only heard the “traditional” Jewish answers to this question, Maimonides’s

answer might come as a shock. Best to sit down and buckle up!

The

Purpose of the Universe

Maimonides’s

treatment of this topic takes place in the context of an even larger question:

What is the purpose of the universe as a whole?

He

begins by challenging the notion that the universe was created for the sake of human

beings. He argues that the universe is far too vast to be necessary for the

human species, which is like a mere drop in the sea. (See the recent images

taken by the Webb telescope released by NASA in July 2022.) And if a person

claimed that all the planets, stars, and galaxies in the universe aren’t necessary

for humans but nonetheless benefit us, the burden of proof would be on that

person to explain how. (If Maimonides were playing chess, this is the

first place he’d say, “Check.”)

Next,

he refutes the common religious answer to our initial question, namely, that

the purpose of man is to serve God. He writes: “Even if the universe

existed for man's sake and man existed for the purpose of serving God, as has

been mentioned, the question remains: What is the purpose of serving God? God

does not become more perfect if all His creatures serve Him and comprehend Him

as far as possible, nor would He lose anything if nothing existed beside Him.”

In other words, God is perfect and has no needs; therefore, the purpose of the

universe and of man cannot possibly be for His sake. (“Check again.”)

At

this point, it would seem there is only one move left for the religious

individual to make: the universe exists for us, we exist to serve God, and our

service of God is not for His sake, but for our sake. Maimonides

serves this view up, then smacks it down: “It might perhaps be replied that the

service of God is not intended for God's perfection, but for our own

perfection; it is good for us and perfects us. But then the question might be

repeated: What is the purpose of our perfection?” (“Check yet again.”)

And

this is where he drops the M-bomb (short for “Maimonides bomb”). Ready for it? According

to Maimonides, life has no purpose. (“Checkmate.” Mic drop.)

The

Purpose of Life (or Lack Thereof)

Many of us were taught that each person was given a special

mission to accomplish which is their purpose in life, but Maimonides doesn’t

buy that. Nor does he buy the other common answers, such as “God created

the universe because He wanted to bestow His kindness” or “God created us in

order to reward our service,” both of which run into the problems mentioned

above.

But

before you tip over your king and careen into the nihilistic void, allow me to unpack

Maimonides’s nuanced position.

Think

about how we relate to the question, “What is the purpose of X?” We ask this

question when the utility of an entity is not readily apparent. Consider the

following scenario. You see me holding an unfamiliar gadget. You ask me, “What

is that for?” and I answer: “Oh, this? This thing has no purpose.” You might

reply, “Then what’s the point? What good is it?” In other words, you assume

that if it has no purpose, then it is not good.

But

that conclusion isn’t necessarily warranted. In truth, there are two possibilities

for why (or how) something “has no purpose.” One possibility is that the entity

is, indeed, useless. Its existence lacks justification. It is a means to no end

whatsoever. The other possibility is that its existence is an end in and of

itself. It doesn’t need any purpose outside of itself to justify its own

existence because its existence is intrinsically good.

That is

the sense in which Maimonides would say that life has no purpose: because

existence is good, in and of itself.

The

Basis in Torah

This

view is borne out in the opening chapter of Genesis. The phrase “and

God saw that it was good” appears six times in the account of creation.

If the Torah had withheld this declaration of goodness until after the creation

of man, one might be justified in concluding that man is the purpose of the

universe. But that's not what the Torah says. God creates light and deems it

"good." He separates the seas and dry land and deems this

"good." He creates vegetation and trees and deems them "good."

And the luminaries, and the fish, and the birds, and so on.

Maimonides

understands this to mean that each and every component of the universe is good

simply by virtue of its existence. And when the account of creation ends with “God

saw everything that He had made and behold! it was exceedingly good” (Genesis

1:31), this means that the universe has no purpose outside of itself. According

to Judaism, existence in accordance with the will and wisdom of the Creator is

the only standard by which goodness is measured. [2]

Now

we can rephrase the answer to our original question in a more uplifting way.

What is the purpose of life? To exist! To live! Life is inherently good!

You don’t need any special, personalized mission to imbue your life with value

because your life has intrinsic value!

And that

is the end of the story … almost.

The

Anomaly of Humanity

On Day Six, God creates the land

animals and declares them to be good. Then He creates man and woman but does not

declare them to be good. Why not? The answer lies in the essential difference

between humans and all other phenomena in the universe. What is that

difference? Free will.

We are the only creations that have

free will and who can choose to disobey God. The Sages express this in the

Tamludic dictum: “Everything is in the hands of heaven except for the fear of

heaven” (Berachos 33b), which Maimonides explains to be a reference to free will.

All other creations in the universe are “programmed” to exist in line with the

will and wisdom of the Creator, without any possibility of deviation, and are

therefore good “by default.” We humans can deviate. We can choose to

live like animals, neglecting our unique capacity for abstract intellection, or

we can attempt to live like angels, neglecting our physical and psychological

needs. Both paths run contrary to our design, and therefore lead to

self-destruction.

Rather, we humans must choose

to live in line with the will and wisdom of the Creator. God does not declare

man and woman to be good because this goodness isn’t guaranteed. The

sociologist, Eric Hoffer, wrote: “Animals can learn, but it is not by learning

that they become dogs, cats, or horses. Only man has to learn to become what he

is supposed to be.” We must learn what it means to be human, and to consciously

align ourselves with that ideal to the greatest extent possible in order to

thrive.

[This is where the Torah comes into

the picture. Gersonides (a.k.a. Ralbag, 1288-1344 C.E.) defines Torah as “a

God-given regimen that brings those who practice it properly to true success.”

Perhaps it would be more accurate to translate “true success” as “true human

flourishing” – to find fulfillment by living in line with our true nature as

truth-seeking beings devoted to seeking knowledge and practicing kindness,

righteousness, and justice on earth, in harmony with ourselves and our fellow

human beings. How the Torah serves this function is a topic for another article

…]

The Purpose of Your Life

And this is where the notion of individual

purpose finds its place. According to Maimonides, there is no extrinsic

purpose to any individual’s life as an individual. We all share a common

mission: to live in a manner which actualizes the human potential inherent in

our nature. However, this actualization will play out differently based on our

strengths, weaknesses, and individual differences, as determined by nature and

nurture.

For example, Moses, Rabbi Akiva, and

I belong to the same species and aspire to the same standard of human “goodness,”

but since each of us possesses a different set of potentialities and lives in a

different set of circumstances, each of us will have a different path of

“goodness” to follow.

Here the maxim “know thyself” takes

on additional significance: to live a “good life” we must know ourselves as

humans, but we must also know ourselves as individuals, so that we

can actualize our individual potentialities in accordance with the blueprint of

universal human nature.

Conclusion

Let us conclude with a summary of

the main points. What is the purpose of life? According to Maimonides, life has

no purpose – not because it is pointless, but because existence in line with

the will and wisdom of the Creator is inherently good. This is true for

everything in the universe, including for us, but unlike the other creations,

we must learn what it means to be human and deliberately choose to live that

way in order to live good lives. And because each of us is different, we must

acquire enough self-knowledge to actualize our individual human potentialities,

thereby making each of our lives worth living.

Afterword

After sending in my rough

draft, I received an email from one of the editors (who is a rabbi) saying, “Thank

you very much for this excellent article.” I asked a few questions about matters

of style, which he answered. The only suggestion he had about the substance of

the article was to omit the paragraph about the role of Torah, saying that “a

separate piece on ‘What is Judaism?’ would do very well.” I made these cosmetic

changes and then submitted my final draft.

After not hearing back from

either of my contacts for a week, I emailed them to ask whether there are other

changes I should make. The editor who initially contacted me apologized for the

delay (explaining that her response had been sitting in her draft folder), and

then went on to say:

Even though

we personally enjoyed it, our editor in chief flagged it and shared the piece

with the Rosh HaYeshiva and they got back to us and said that they feel the

article is "confusing and misleading." Unfortunately the whole

approach doesn't work for them. We do

sincerely thank you for your time and effort and will of course be remunerating

you for it.

I would have appreciated it if

the editor in chief and/or the Rosh HaYeshiva had elaborated on what they meant

by “confusing and misleading,” but I wouldn’t expect them to take the time to provide

detailed feedback to a total stranger about a piece they decided not to use. Of

course, this left me with two options: (1) to speculate about what they might have

meant, and (2) to solicit feedback from other people.

My speculations are straightforward: I suspect they deemed the article “misleading” because they fundamentally disagree with

what I wrote, and they called it “confusing” because since they couldn’t openly

denounce the Rambam for his views, they instead placed the blame on my presentation

of his views.

What, exactly, do I think they

found so disagreeable? It could be any of several points: that the universe wasn’t

created for man, that man doesn’t exist to serve God, that God doesn't need us for anything, that God did not create

the universe in order to bestow His kindness to man, that the Torah is “merely”

a means of making us good rather than the standard by which goodness is

measured, that Olam ha’Ba isn’t mentioned anywhere in the article, that no

distinction is made between Jews and non-Jews, that I say nothing

about spirituality, etc.

But if I had to bet money on which

sentence they found to be the most objectionable, it would be this: “Many of us

were taught that each person was given a special mission to accomplish which is

their purpose in life, but Maimonides doesn’t buy that.” Since I was writing

for an audience of laypeople, I didn’t refer to this notion by its commonly

used Hebrew term “tafkid” or by the related term “tikkun.” I cannot definitively

say how, from where, or when this belief originated, but I do know that it was

popularized by the Hasidic movement to the point where it can now be described

as “mainstream.” For example, here’s an excerpt from the book “The Garden of

Emunah” (2006) by Rabbi Shalom Arush, a Breslov Hasid, translated into English

by Rabbi Lazer Brody:

Each of us

comes to this earth for the express purpose of fulfilling a mission. Longevity

depends on the task we have to complete. One’s death – even in a sudden tragedy

or accident – is always the result of Hashem’s personal decision. Some live for

twenty years and others for one hundred years, but we all eventually leave this

earth at the precise moment that Hashem decides. A mind-boggling set of Divine

considerations influences the circumstances of a person’s life and longevity –

the person’s deeds, former lives, public edicts, and other criteria that defy

our understanding.

Some souls

come to this earth for a short and specific tikkun, and then return to the

upper worlds. Such souls are usually remarkably special people, with little or

no evil inclination, gentle, kind, and pleasant. Therefore, don’t be surprised

when you hear of young upright people that die suddenly; they’ve simply

completed their tikkun – their soul correction and mission on earth. (p.44)

As you can see from just this

short excerpt – and certainly from the rest of the book – the notion of a

Divinely ordained mission in life is inextricably bound up with many other

fundamental doctrines: hashgachah pratis (individual Divine providence), sachar

v’onesh (reward and punishment), tzadik v’ra lo (“Why do bad things happen to

good people?”), bitachon (trust in God), and more. To question, challenge, or deny

the notion of an individual purpose in life is to threaten these foundational beliefs. And

that’s essentially what I did by presenting the Rambam’s view in the manner that

I did.

Of course, I knew I was doing

this when I wrote the article. I knew that their readership would be unlikely

to hear this idea from anyone else, and I know how powerful this idea can be.

In fact, the first time I heard this answer given in this exact way was at a

Q&A with high school students held by my Rosh ha’Yeshiva. I still remember

the feeling that reverberated through the room when he said, “life has no

purpose,” and then went on to explain the ideas in this article. (You

can listen to the recording by clicking here and skipping to 24 minutes; note

that my Rosh ha’Yeshiva had laryngitis at the time.) I wanted to replicate that

experience as much as I could in my article because I know that it will

resonate with others the same way it resonated with me and with all the other

students who were present at that Q&A.

This is also why I left the

reader “an out” by underscoring that this is the view of Maimonides. I

did not claim that this view is unanimous. I included

the phrase “according to Maimonides” in the title. I repeatedly stressed

throughout the article that this is all “according to Maimonides.” I did this so

that if someone felt threatened, they could dismiss it by saying, “That’s just the Rambam's view.”

And this is why I think it is

misleading to call my article “misleading.” It would be misleading if I misrepresented

the Rambam’s view. To my knowledge, I didn’t do that. I could be wrong, though,

which is why I’m sharing this article and the feedback publicly. If I’ve

misunderstood the Rambam’s position, then I’d like to know how – especially on

such a fundamental issue as the purpose of life.

To reiterate: I can see how a

person might consider this article “misleading” if they felt it would lead the

reader astray from (what they maintain is) the truth. But “confusing”? I

thought I did a decent job of presenting this idea clearly, which is another

reason I’d like feedback. I would especially like to hear feedback from someone

who says: “I completely understand what you are saying and you presented these

ideas very clearly, but I think you are 100% incorrect.” At least that way I’ll

know that the reader isn’t biased by their agreement with what they've read.

And so, my readers and

listeners, what do you think? Do you find this article to be confusing

and/or misleading? If so, why? What other thoughts, questions, and critiques do

you have? I'm all ears.

___________________________________________________________________________________

If you've gained from what you've learned here, please consider contributing to my Patreon at www.patreon.com/rabbischneeweiss. Alternatively, if you would like to make a direct contribution to the "Rabbi Schneeweiss Torah Content Fund," my Venmo is @Matt-Schneeweiss, and my Zelle and PayPal are mattschneeweiss at gmail.com. Even a small contribution goes a long way to covering the costs of my podcasts, and will provide me with the financial freedom to produce even more Torah content for you.

If you would like to sponsor a day's or a week's worth of content, or if you are interested in enlisting my services as a teacher or tutor, you can reach me at rabbischneeweiss at gmail.com. Thank you to my listeners for listening, thank you to my readers for reading, and thank you to my supporters for supporting my efforts to make Torah ideas available and accessible to everyone.

.png)